It is a woman's right to make an informed choice regarding where she wishes to give birth (Birthrights, 2013). Globally, it is recommended that women's individual health needs should be taken into consideration when designing and implementing maternity services and that women should be offered more choice (World Health Organization [WHO], 2016). Choices regarding place of birth can be complex, important and difficult life decisions (Edwards, 2008). Women should be given the opportunity to have a birth experience that is positive and choice regarding place of birth is a crucial factor in determining birth experience (Bryanton et al, 2008).

The WHO guideline states that most women want a physiological labour and birth, and to have a sense of personal achievement and control through involvement in decision-making, even when medical interventions are needed or wanted (WHO, 2018). It also highlights how woman-centred care can optimise the quality of labour and childbirth care through a holistic, human rights-based approach. Midwifery-led care (MLC) models that encourage continuity-of-care, in which a known midwife or small group of known midwives supports a woman throughout the antenatal, intrapartum and postnatal continuum, are recommended for all pregnant women (WHO, 2018). MLC models of care aim to offer increased control and choice for women and their families during and after pregnancy (Walsh and Devane, 2012).

An important aspect of MLC is that it promotes continuity of carer. This has many documented benefits, including women being 24% less likely to experience preterm birth, 19% less likely to lose their baby before 24 weeks' gestation, and 16% less likely to lose their baby at any gestation (Sandall et al, 2013).

The MLC model has been rigorously evaluated. In addition to being a safe model of care for all women regardless of risk, it also decreases intervention rates, increases continuity of care and maternal satisfaction, and is cost-effective (Marshall, 2005; Walsh and Devane, 2012; Tracy et al, 2015). However, even with a government level policy and processes in place, in reality, women's choices regarding models of care during pregnancy and childbirth are often limited and may be restricted due to MLC not being available to all women because of lack of geographically equitable access (Royal College of Midwives [RCM], 2016).

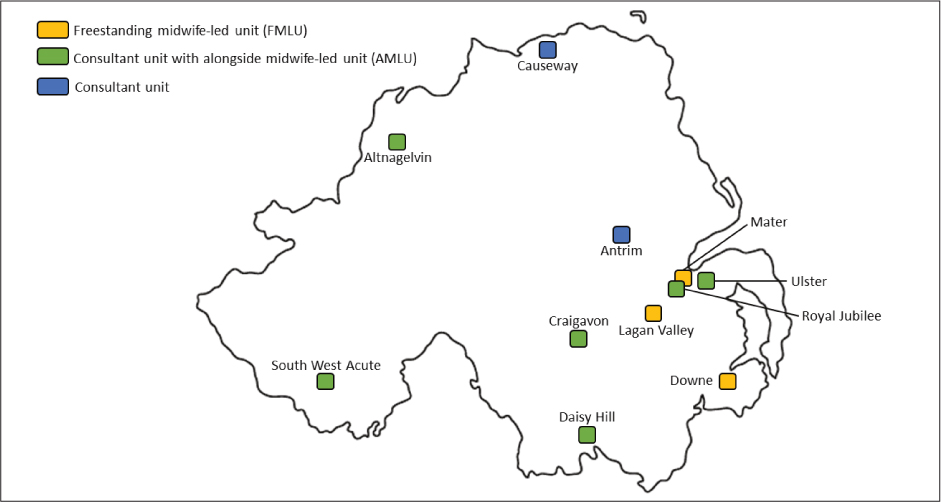

One of the aims of the Northern Ireland Maternity Strategy is to ensure that at least 30% of women give birth at a midwife-led unit (MLU); less than 15% of women give birth in MLUs (Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety, 2012). Since 2010, two freestanding midwife-led units (FMLU) and six alongside midwife-led units (AMLU) have been opened in Northern Ireland. However, not all women in Northern Ireland have all options available to them when choosing where to give birth, due to geographical variability of service provision, (Figure 1).

In a regional study, only 18% of women were aware of all four options for place of birth; at home, in a FMLU, in an AMLU, or in a obstetric-led unit (Alderdice et al, 2016). Just over half of women (57%) felt they had been given enough information to decide where to have their baby (Alderdice et al, 2016). Even when the full range of options is available, individual choices are often determined by a woman's risk profile as assessed by a healthcare provider (Table 1).

| Planned birth in any midwife-led unit (FMLU and AMLU) for women with the following: | Planned birth in AMLU only for women with the following: |

|---|---|

|

|

|

In recent years, an increasing number of pregnant women are deciding where to give birth based on their personal preferences rather than as prescribed by healthcare providers and national guidelines (Hollander et al, 2017). Deciding where to give birth is an important decision for pregnant women. It is considered medically safe for women who have low risk pregnancies to give birth at home (RCM, 2016). However, an increasing number of women with ‘high risk’ pregnancies are choosing to give birth at home, often this means they wish to do so against the advice of the healthcare provider (Hollander et al, 2017).

This trend is not unique to Northern Ireland. Emerging evidence from different countries have examined women's motivations for declining recommended care during pregnancy and after pregnancy (Feeley et al, 2015; Jackson et al, 2016). Often such women have deeply held beliefs, including the belief that interventions and interruptions during labour and birth increase medical risk and that hospitals are not safer than home (Jackson et al, 2012). The interpretation of evidence is strongly influenced by the cadre of healthcare providers making decisions about it; in this case midwifery or obstetrics (Downe, 2016). This has created a situation whereby the advice provided by healthcare providers may not be evidenced based (Lee et al, 2016).

This study explored the perceptions of midwives and obstetricians regarding choice of place of birth for women independent of risk profile in Northern Ireland.

Materials and methods

Study design and setting

A qualitative thematic analysis design was undertaken for this study. Data collection was conducted using semi-structured key informant interviews with seven midwives and five obstetricians working in one of the 11 healthcare facilities in the five health and social care trusts (HSCT) in Northern Ireland. These 11 healthcare facilities in Northern Ireland serve an estimated population of 430 511 women of reproductive age.

Participants

The participants were purposively selected as information-rich participants with a variety of roles, knowledge and experience in providing care and supporting decision making regarding birth place with women (Cresswell and Plano Clark, 2011). Midwives and obstetricians were included if they were in a senior position working in maternal health, had more than 10 years' experience and were providing hands-on clinical maternity care to women who were making decisions about place of birth.

This specific criterion was selected because women are referred to these senior healthcare providers to discuss decisions surrounding place of birth if additional support was identified during routine care. Twenty eligible participants were approached to participate in the study and all agreed to take part. The participants were recruited sequentially until data saturation was met and no new themes were emerging throughout the interviews (Fusch and Ness, 2015). Twelve interviews were undertaken.

Of the 12 participants recruited to the study, nine were female and three were male. They were all senior healthcare providers: midwives (n=7) and obstetricians (n=5). Participants had varied experience and had worked in different hospitals within the HSCT and each of the birth settings (AMLU, FMLU, obstetric-led unit [OLU] and home birth) were represented. Three of the midwives had experience working in FMLUs and home birth settings, four in AMLUs and all of the midwives and obstetricians had experience working in OLUs.

Data collection

A topic guide was developed to guide the key informant interviews and was piloted with several senior research midwives. It was subsequently refined to improve its quality and transferability. The topic guide served as a flexible tool to facilitate the interviewers in obtaining the participants' answers while ensuring that the interview remained on topic. It also acted as a cue to ask more probing questions to further understand participants' perceptions. Prior to interview, all eligible participants were approached via email and given verbal and written information regarding the study, including a brief overview of the research aims and objectives. An interview appointment was then scheduled for a time convenient for the participant.

All participants were interviewed in English using an interview guide (Table 2), with the average interview lasting 45 minutes. Interviews were conducted face-to-face, recorded on a password-protected digital recording device and transcribed upon completion. All interviewees were given a unique identification number to ensure anonymity. All interviews were held in a location of the participants' choice – either at their workplace or home. To maintain confidentiality, the interviews were carried out in private rooms and the recording device was accessible to only the primary researcher.

| Choice of place of birth regardless of risk profile: views of healthcare providers and policy makers in a Health and Social Care Trust (HSCT) in Northern Ireland. Semi-structured interviews: interview guide |

|---|

| Introductory questions |

| What are the current birth places available to women within the HSCT? |

| How can staff ensure women are fully informed/counselled of the benefits/risks/implications of their choices regarding place of birth before making decisions relating to this? To your knowledge, does this happen? |

| In your opinion, does a healthcare provider's personal opinion/ethos impact on a woman's choices regarding place of birth? |

| Key questions |

| In your opinion, should woman's risk profile should limit/impact her choice in regards to place of birth and why? |

| From your experience, why do high-risk women choose to birth at home or within an MLU? |

| If a woman does not meet the criteria for admission to an MLU, how does the service cater for her choices? |

Analysis

Transcribed interviews were reviewed independently by two researchers. Codes for analysis were decided upon after consensus. The interviews were uploaded using NVivo software (NVivo 12, 2010) and the data were analysed using a six-phase inductive thematic approach (Hsieh HF, Shannon SE).

The transcripts were read twice to identify initial ideas and meanings. The two researchers then generated an initial set of codes. These codes were sorted into themes and relevant coded data were selected within the themes. The themes were refined and either combined or discarded after discussion. Finally, the two researchers defined and agreed upon the final theme reported in this paper.

Results

Five main themes emerged during the data analysis: informed decision-making among pregnant women; understanding and judgement of risk; autonomy and choice; culture of control and fear; and human rights with regard to childbirth. Similarities and differences of perceptions between the cadres of healthcare providers are also discussed.

Informed decision-making

Informed decision-making regarding place of birth was the first theme that emerged. Many of the participants felt that women were not fully informed about the options they had regarding place of birth.

‘There are so many barriers to women getting that information. Not just in terms of the personal opinions of the individual care giver, but in terms of the HSCT policies and guidelines.’

‘The problem is that the people making decisions aren't making decisions based on individual women's preferences.’

Fragmented care, where women are seen by many different healthcare providers throughout their pregnancy, and time constraints at antenatal clinics were identified as possible reasons why women are not fully informed about all their options for where they could give birth.

‘I think partially it is down to time constraints in appointments. If you have a clinic and you're seeing 10 or 12 women, you will have time constraints there, so sometimes you can't fully inform each woman.’

‘I don't think women are given their options. I think midwives at the current booking interview … it is so intense, and they have so much other stuff they must cover.’

It was acknowledged that a healthcare provider's opinion could impact upon a woman's decision-making regarding place of birth.

‘I think how we tailor the information can affect what choice a woman makes.’

‘The simplest example is that a woman says it is way too dangerous [to birth in a MLU] and you don't make the effort to educate her at that point because you yourself are afraid then your opinions definitely have influenced the woman's choice and she isn't fully informed.’

All the participants mentioned that within the current system, women with risk factors were not able to access MLUs. They are advised that they need to deliver in the OLU and this impacts on their choices surrounding place of birth, with some women choosing to birth at home.

‘You know she'll be excluded from giving birth in an MLU and then she exercises her right to a home birth which is kind of crazy in a sense.’

‘You are not offering the full choices unless you allow every woman who, after being informed, wants that choice – you close the doors and say, “No, but not you”. Everybody that you give the fully informed information and says,“I want to go there” – they should be offered a place.’

Understanding and assessment of risk

Assessment and understanding of risk in pregnancy, as perceived by both healthcare providers and pregnant women was another theme that emerged. The language used to categorise women was discussed.

‘I object to “low risk” and “high risk” because that is essentially two different types of women, but it's like a rainbow – not black and white.’

‘Risk as a concept gets blown out of proportion. The language becomes very risk focused without, I think, sometimes the understanding of what we are talking about.’

There was general awareness and understanding among all participants regarding how women and healthcare providers quantified risk. Several of the participants said they understood that there was often a difference between how risk is categorised by women, healthcare providers and the system.

‘We are just obsessed with risk. Obsessed with risk. We just can't seem to see the downsides of our interventions.’

‘Women make risky choices, but they are independent people. They are not putting their baby at risk, they are just looking at risk differently from the way we look at it.’

It was also recognised that it may be challenging for women to understand and align specific risks to themselves and that sometimes the healthcare provider's understanding of risk could influence the decision.

‘Women need to understand the relative risks of what we are talking about and that is quite specific information and requires an in-depth discussion. It's not easy to explain.’

‘I would feel more comfortable with a primigravida who was in the alongside midwifery-led unit than a free-standing midwifery led unit, because the risk of transfer is slightly higher risk of poorer outcomes. Why take that chance?’

A number of participants felt that discussion surrounding risk was very subjective and they felt that more women were being labelled as high risk without evidence to back up their risk status.

‘The whole discussion of risks is totally skewed. In my experience, the only time women are told about the risks of intervention is that specific circumstance where choosing a [caesarean] section is deemed to be medically unnecessary.’

‘I don't see how 75% of women in this trust could be considered high risk. The risk profile is changing, people are becoming older, obese, diabetic – but not 75% of them – so there should be more people able to access midwifery-led care and should be supported in that choice. Whether we feel it is the most safe place for them, it is what they feel, not what we feel.’

Autonomy and control

Within the current system in the HSCT studied, once a woman has been identified to be ‘at risk’, she is always referred to, and placed under the care of an obstetrician.

‘If someone has a high-risk profile that would be identified, they would be seen by a consultant. So even if they were to request midwifery-led care when they were coming up to the hospital, it would be in a consultant clinic.’

‘Women [high risk] are being told point blank that they can't go to MLU – you have to go to an obstetric unit … So, their choices are not being respected and they are not being given the option.’

However, 10 participants highlighted that all women should be supported in their choices even if they were high risk, and it was part of their role to support women when they had made a fully informed decision and that partnership was essential.

‘I think if they are given informed choice and they make that choice, we should support them, and not treat women as if they don't know what is best for them.’

Conversely two participants stated that they did not believe that a woman who is considered high risk should be given a choice as to where she could give birth.

‘If someone does fall into a high-risk category, then it is important for us to try and encourage the patient to be facilitated [to give birth] in the appropriate place, rather than simply accept a wish of theirs to be delivered in a place that is clearly inappropriate for their risk profile.’

Some participants noted that women who were deemed to be high risk sometimes made a choice to give birth at a place not advised by the healthcare provider in order to maintain control.

‘I think high-risk women that choose to birth at home feel that they have no choice and don't want to be in an obstetric unit. Because of their risk factors they won't be allowed to access MLU, so their only option is a home birth.’

A participant stated that women who choose to give birth at a place contrary to that advised in the guidelines are given more subsequent appointments by healthcare providers than other women and some women have then reported feeling ‘bullied’ into making the ‘right’ choice.

‘If a woman has risk factors and wants to do something that we don't think is ideal, the machinery is activated to change her mind. It is not activated to make it safer for her to do what she wants. It is directed against getting her to change her mind.’

Culture of fear surrounding childbirth

Another theme was a culture of fear surrounding childbirth in Northern Ireland. In many of the interviews, the participants mentioned that cultural factors and the hierarchal health system had an impact on how women made decisions. Northern Ireland is unique in that it has private antenatal healthcare, but no private hospital for women to give birth in. All intrapartum care is provided within the HSCT. This was highlighted as a factor when women choose to give birth in an OLU if they were low risk, as their lead caregiver during pregnancy was an obstetrician.

‘I think there is a fear of birth definitely and I think, if I'm not mistaken, statistically she [a low-risk woman] is more likely to choose that [birth in an OLU] if she is having private care.‘

‘I know one private consultant who believes that no woman should have to pass a baby vaginally. So, if that doesn't influence the mother's choice, I don't know what would.’

Cultural factors specific to Northern Ireland were seen to have an influencing factor on women's choice regarding place of birth. One participant who has worked across Ireland and England stated:

‘Most doctors in Northern Ireland – whatever they might say – honestly believe that babies should be born in hospital and that obviously transmits. In Northern Ireland, what doctors say counts much more than what midwives say.’

Media was seen as portraying a negative view of childbirth and participants stated that this influenced pregnant women's decision-making in relation to birth choices. Participants mentioned fear as being a prevalent factor during pregnancy and felt this often impacted on how women choose where to give birth or indeed where to access antenatal care.

‘I think women are fearful. Birth is portrayed as a painful, frightening, hospitalising experience.’

‘There is a very strong cultural belief set around birth being dangerous. We have been telling women for 100 years that birth is dangerous and it is very hard to overturn that. That is the more pervasive fear of birth.’

The rights-based approach

Another theme was the legal aspects of a woman's right to choose place of birth, regardless of whether or not risk factors are identified. Discussions emerged surrounding legal reasons why women should not be provided with information and choose to give birth where they wanted, even if risk factors were identified. There was a varied response, with some of the participants revealing it to be a complicated issue.

‘I don't know of any legal reason why a woman can't make a fully informed choice unless she is not of sound mind, so it would be her human right to be offered the full range of choices.’

‘I find it very difficult when midwives put up objections and say I am going to be brought to court if I support a woman to birth wherever she wants. The woman made an informed choice. She is an adult.’

It was evident that some of the healthcare providers felt that the HSCT was not supportive of a woman's right to choose the place of birth independent of risk factors.

‘As a trust, it is very much no, you can't do that. I felt it has been like that anyway. It is just like, no, that is against the trust policy or is a litigation issue.’

‘There is fear of litigation which seems to be a big driving force for the trusts. The fear-based risk adverse culture becomes pervasive if you are not careful.’

Discussion

It is very appropriate that women receive evidence-based information about the circumstances in which a particular birth setting may be more or less safe and appropriate. However, our findings reveal that an issue arises when the woman disagrees with the guidelines and wishes to birth in a setting that is not recommended for her. Where there is conflict regarding choice of birth place, this is still largely a taboo subject.

Healthcare providers do not routinely offer women choice regarding place of birth once women have been categorised as high or low risk. Women are signposted to the place of birth that the guidelines recommend. However, this can indicate a reliance on risk calculations that are abstract and not understood by women because they are removed from the lived experience of pregnant women who have birthed in MLUs (Holten and de Miranda, 2016).

The findings showed that participants felt that women without risk factors were not making fully informed decisions when choosing to birth in OLUs, but interestingly all the participants, regardless of profession, supported a woman's choice to make this decision. It was not the same for woman with risk factors who choose to birth in MLUs or at home. In this study, more than half of the participants (n=9) interviewed expressed a desire to provide support for women, even if women make a choice that could be considered medically unsafe. All the midwives interviewed would support women to choose place of birth regardless of risk factors and believe that women who make these decisions are fully informed.

If a midwife or obstetrician practises outside these guidelines, they feel that they are open to criticism and blame, so often they operate within carefully reviewed and prescribed care (Behruzi et al, 2010). The findings of this study show that a healthcare provider's wish to support women to choose place of birth was easily unsettled by the HSCT's risk technologies and risk structure. Some of the participants interviewed felt that a punitive blame culture existed in the system in which they worked. In many other healthcare settings, if patients decide not to adhere to advised interventions, such as chemotherapy or surgery for symptom relief in palliative care, this is accepted as an individual's choice over their treatment (British Institute of Human Rights, 2016).

This research reveals that a system has emerged in maternity care where women are not able to plan their own care or birth without having to access all of the prescribed care and adhere to guidelines (Edwards and Kirkham, 2013). The findings show that practice within the HSCT where the research took place is different from other settings in the UK. This was a concern that was highlighted by the findings and was explained by the dominance of the medical model in the psyche of the population in Northern Ireland.

When reporting the findings, we identified the quotes by healthcare provider cadre. We felt that this was important as we could then assess differences in perceptions regarding choice of place of birth between cadres, if they were identified. The majority (n=4) of the obstetricians who were interviewed felt that women should always adhere to the trust policies and guidance of the healthcare providers. All the midwives believed that women should be given a real and informed choice, but they felt that the current system did not provide women with that choice.

All the midwives highlighted that, despite the best intentions, to care for women contrary to the prescribed guidelines and policy documents was very challenging. They discussed the personal impact this has had and said they felt that the system is such that women cannot really make decisions without some control being exerted over them by midwives and obstetricians.

Many of the midwives and obstetricians stated that working in partnership with women and having a multidisciplinary approach was an important part of the decision-making process. Our study illustrates that counselling women who disagree with the recommended guidelines demands time, interest and good communication skills. It also requires a joint effort between the multidisciplinary team. The majority of the midwives (n=6) reported feeling helpless in their attempts to support women whose decision regarding place of birth is at odds with guidelines because of a lack of time, resources, senior support and knowledge regarding legal implications and the complex context in which this occurs.

Although midwives and obstetricians within the study had different perceptions about the topic under study and job roles and responsibilities, it was acknowledged that ultimately everyone wanted high-quality care for the pregnant women and unborn baby. The participants agreed that women do not want to be coerced into decision or bullied, so working in partnership and supporting women in their choices ensures a safe experience for all.

How does this study relate to other literature?

This study adds understanding to how risk is understood and acted on in maternity care in Northern Ireland. There are increasing restrictions placed on women and healthcare providers regarding choice of place of birth due to concerns around safety. These are often primarily legal concerns rather than health concerns (British institute of Human rights, 2016). Dahlen et al (2012) illustrate that healthcare provider's advice and information provided to women about birth place options can be influenced by the women's decision to comply with guidelines. We also found this. Our study showed that debate about a woman's right to choose where she gives birth is about more than just place of birth, it raises deeper and more complex issues such as the right of women to have control during childbirth, and, the rejection of the medical model which often focuses on a pathological view of pregnancy and childbirth – themes that are highlighted in other studies (Mander 2009; Dahlen et al, 2011; Dannaway and Dietz, 2014).

In our study, communication between healthcare providers and women was seen as essential to decision making related to place of birth. This echoes other studies which show that pregnant women remain positive regarding communication with healthcare providers if the advice that is given regarding place of birth is unbiased and if the healthcare provider acknowledges and takes into account the concerns of the woman herself, providing individualised care (Feeley and Thompson, 2016).

Our study reveals that it is essential that healthcare providers do not perceive women who choose not to follow their advice as ‘challenging’, but instead provide safe advice and care that is respectful of the woman's own values and does not create barriers to communication. This is similar to other studies which show that effective communication and engagement among healthcare providers, managers, women and advocates working within the women's groups and women's rights movements are essential to ensure that maternity care is responsive to women's preferences and needs. (Dannaway and Dietz, 2012; Kruske et al, 2013; Hill, 2014; WHO, 2018).

Strengths and limitations

This study extends the understanding of how supporting women to choose place of birth impacts upon both healthcare providers and pregnant women, and, what the perceived barriers which exist in the health system to facilitate women being able to have a fully informed choice. Participants in the interviews provided rich, nuanced and differentiated accounts of their everyday experiences supporting women to make decision regarding place of birth regardless of risk profile.

Participants included midwives and obstetricians who were working clinically across all of the birth settings in the HSCT, home, FMLU, AMLU and OLU. This gives the study a comprehensive view of the clinical conditions and practice occurring in the health and social care trust at the time of the study. Interviewing a range of participants with varied levels of experience, who had spent time in different clinical settings and from different healthcare facilities in the HSCT, enabled a degree of transferability to be achieved. However, this study included mainly senior obstetricians and midwives in managerial roles and more junior healthcare providers may have alternative perspectives or different insights. As this study was conducted in one HSCT due to the scope of the study, there was a degree of selection bias in the sampling. As the main researcher was a midwife working within the HSCT under study the data was reviewed independently by two researchers to limit bias.

Conclusion

Every woman deserves and needs to be supported during pregnancy and at the time of birth by a healthcare provider who they can trust. This study reveals that pregnant women have the right to make autonomous decisions about her pregnancy and childbirth. The results show that shared decision making, open communication, and collaboration will ensure that all stakeholders are supported, and will support the creation of a culture where women are supported to make informed decisions about their care during pregnancy and birth.

The midwives and obstetricians propose solutions to these barriers including a human rights-based approach which is about health and not isolated pathologies and focuses on empowering women to claim their rights, and not merely avoiding maternal morbidity or mortality. More training of healthcare providers, recruitment of a consultant midwife, continual education of women regarding birth choices, increased consultation time, and clear effective referral pathways will improve care for women who are making decisions about place of birth. A designated multidisciplinary clinic, where midwives working in MLUs and home birth settings and obstetricians together see women who have requests that go against recommendations, is another intervention worth considering.